This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implications for the learning function. Part 1 introduced the signature skills demonstrated by experts that separate them from novices.

This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implications for the learning function. Part 1 introduced the signature skills demonstrated by experts that separate them from novices.

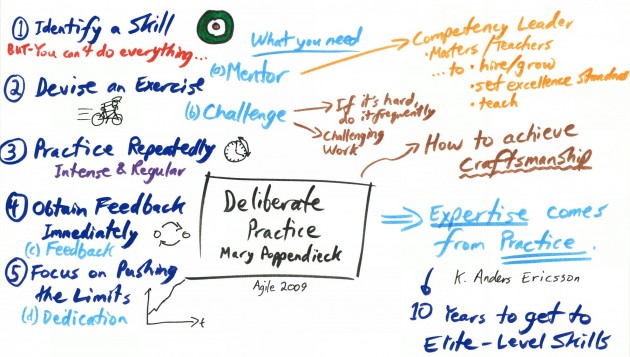

It seems these signatures of expertise are the result of years of effortful, progressive practice on authentic tasks accompanied by relevant feedback and support, with self-reflection and correction. The research team have labeled this activity “Deliberate Practice”. Others have called it deep practice and intentional practice. It entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something you can’t do well—or at all. Six elements for are necessary for practice (or on the job experience) to be “deliberate” practice:

- It must be designed to improve performance. Opportunities for practice must have a goal and evaluation criteria. The goals must be job/role based and authentic. General experience is not sufficient, which is where deliberate practice varies from more laissez-faire approaches to informal learning. Years of everyday experience does not necessarily create an expert. Years of deliberate practice does. See my post Everyday Experience is not Enough for a deeper discussion on this.

- It must be based on authentic tasks. The practice must use real work and be performed in context-on the job. The goal is to compile an experience bank, not a vast list of completed formal training programs.

- The practice must be challenging. The tasks selected for practice must be slightly outside of the learners comfort zone, but not so far out as produce anxiety or panic. Deliberate practice is hard work and stretches a person beyond their current abilities. The experience must involve targeted effort, focus and concentration

- Immediate feedback on results. Accurate and diagnostic feedback must be continuously available both from people (coaches) and the business results produced by the activity. Delayed feedback is also important for actions and decisions with longer term impact as is often the case in knowledge based work.

- Reflection and adjustment. Self-regulatory and metacognitive skills are essential. This includes self-observation, monitoring, and awareness of knowledge and skill gaps. Feedback requires reflection and analysis to inform behaviour change. Experts make mindful choices of their practice activities.

- 10,000 hours. For complex work, ten years seems to be the necessary investment of in deliberate practice to achieve expertise. Malcolm Gladwell drew attention to the 10,000 hour rule in his book Outliers and it is one of the most robust findings in this research. It poses a real challenge for our event based training culture. Of course the less complex the work, the less time required to develop expertise.

If we aspire to evidence-based approaches to learning it’s hard to ignore this body of research. Among other things, it challenges us to consider how we can better support the novice to expert journey, embed learning and practice in the job, design experience to include deliberate practice, build tacit knowledge, and build rich feedback into our organizations.

Fortunately we have a number of approaches available to us that align well to the conditions of deliberate practice. I’ll outline those approaches in Part 3.

Here is a nice illustration of the key process and concepts of deliberate practice courtesy of Michael Sahota:

[…] These are skills we want in all employees. At times they seem like they come from an innate ability or deep “competency” unachievable by others. However the research shows that while natural ability may play a small role, practice and experience are far more significant. The nature of this experience is critical. “Practice makes perfect” is only true for practice of a certain type which I describe in part 2. […]

I’m sorry but there’s no 10000 hour rule.

Gladwell misinterpreted Ericsson. by the way. Strange you did not mention Anders Ericsson here….

I reference Ericsson in part 1 of the three part post. I mention that the 10,000 hours would vary by the complexity of the task. 10,000 hours does feel overly prescriptive, but Ericsson’s research support practice in that range for complex skills. I think everyone agrees at this point that Gladwell took some liberties with his interpretation of the research, but it has also become fashionable to reject Ericsson’s data in favour of talent based perspectives. There is some data supporting the role of talent. Ericsson has presented his counter arguments effectively….and so goes the scientific discourse.

[…] Deliberate practice: The path to developing expertise This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implic… […]

[…] Deliberate practice: The path to developing expertise This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implic… […]

[…] Part 1 introduced the signature skills demonstrated by experts that separate them from novices. Part 2 presented the key features of effective practice–Deliberate Practice. This post gets to […]

[…] This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implications for the learning function. Part 1 introduced t… […]

[…] Deliberate practice: The path to developing expertise This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implic… […]

[…] This is a variation of an article I prepared for CSTD and HRVoice, summarizing important research on how practice develops expertise and implications for the learning function. Part 1 introduced t… […]

[…] Photo credits: Øyvind Hellenes, Performance X Design […]

[…] Expertise is the result of effortful, progressive practice on authentic tasks accompanied by relevant feedback and support, with self-reflection and correction. The research team have labeled this activity “Deliberate Practice”. Others have called it deep practice and intentional practice. It entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something. […]

[…] & Development of Expertise: Part 1 – Part 2 – Part […]