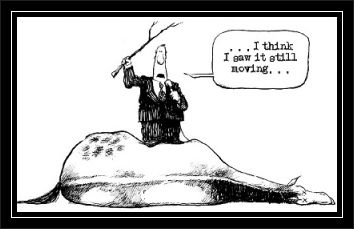

I’m at risk of flogging a very dead horse here, but some recent posts from Ellen Wagner (What is it about ADDIE that makes people so cranky?) and Donald Clark (The evolving dynamics of ISD and Extending ISD through Plug and Play) got me thinking about instructional design process and ADDIE in particular (please don’t run away!).

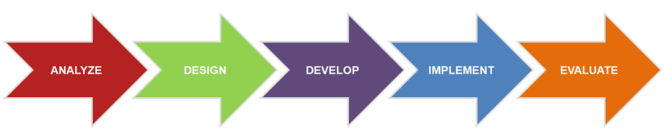

Ellen’s post focused on how Learning Designers on a twitter discussion got “cranky” at the first mention of the ADDIE process (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation and Evaluation). On the Twitter #Lrnchat session participants had a gag response to the to the mere mention of ADDIE (sound familiar?). Don responded with some great comments on how ISD (ADDIE) has evolved and adapted.

Much of my career has been involved in applying ADDIE in some form or other and I’ve landed on a conflicted LOVE/HATE relationship with it to which you, lucky reader, will now be subjected.

HATE (Phase A, Step 3.2.6)

Throughout the 90’s many Instructional Designers and e-Learning Developers (me included) grew disgruntled with ADDIE (and its parent process Instructional Systems Design—ISD) as training struggled to keep up with business demands for speed and quality and as we observed process innovations in software and product development field (Rapid Application Development, Iterative prototyping etc).

In 2001 that frustration was given voice in the seminal article “The Attack on ISD” by Jack Gordon and Ron Zemke in Training Magazine (see here for a follow-up)

The article cited four main concerns:

- ISD is too slow and clumsy to meet today’s training challenges

- There’s no “there” there. (It aspires to be a science but fails on many fronts)

- Used as directed, it produces bad solutions

- It clings to the wrong world view

I have memories of early projects, driven by mindless adherence to ISD, where I learned the hard way, the truth in each of these assertions. As an example of what not to do and a guard against blowing my brains out in future projects, for years I have kept an old Gagne style “instructional objective” from an early military project that would make your eyes burn.

Early ISD/ADDIE aspired to be an engineering model. Follow it precisely and you would produce repeatable outcomes. The engineering model assumes a “one best way” and the one best way of the time was grounded in the science of behavioral psychology and general systems theory. The “one best way” thinking appealed to the bureaucratic style of the times but it couldn’t be more of an anathema to the current crop of learning designers, especially those focused on more social and constructivist approaches to learning. And they are right.

Another criticism of ADDIE I have parallels Ellen’s comments. Adherents and crankites alike view ADDIE as an “instructional design” methodology when in fact it should be viewed more as a project management process for learning projects. Viewing Instructional Design as synonymous with ADDIE does both a disservice. There is loads of ID going on inside ADDIE but it is primarily in the Design phase of the process, and it can be much more creative than the original model prescribes.

In the end, the Achilles heel of formal ISD/ADDIE rests in its prescriptive posture and foundation in behavioural psychology. Behavioural psychology and performance technology–its extension in the workplace–have added greatly to our understanding how to improve human learning at work, but we have learned much since then, and technology has provided tools to both designers and learners that profoundly change the need for a process like ADDIE.

Of course the ADDIE process was (and is) not unique to the learning design profession. For many years the five broad phases of ADDIE were the foundation for the design of most systems. Software engineering, product development, interactive/multimedia development are all based on some variation of the model. Most however have evolved from the linear “waterfall” approach of early models (can’t start the next phase until the previous has been done and approved) to iterative design cycles based on rapid prototyping, customer participation in the process and loads of feedback loops built into the process. And learning/e-learning is no different. It has evolved and continues to evolve to meet the needs of the marketplace. Much of the current gag reaction to ADDIE, like that experienced by Ellen, is based on the old waterfall-linear approach and the assumed instructivist nature of the model. And again the gag is entirely valid.

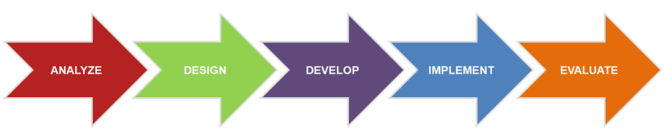

However, if you can break free from the history, preconceptions and robotic application of ADDIE, you may find room for something approaching…

LOVE (Phase B, Step 2.3.7)

I can’t say I ever use ADDIE in its purest form any longer. For e-learning and performance applications, I prefer processes with iterative design and development cycles that are usually a variation of rapid application development process like this one from DSDM.

Or for an example specific to e-learning, this process from Cyber Media Creations nicely visualizes the iterative approach:

Or for the Michael Allen fans out there, his Rapid Development approach described in Creating Successful e-Learning is very good. There is a respectful chapter in the book on the ADDIE limitations and how his system evolved from it.

But at the heart of all these processes are the familiar phases of analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation, albeit cycling through them many times along the way.

For me, ADDIE has become a useful heuristic, not even a process really, but a framework for thinking, coaching instructional designers, and managing learning and e-learning projects. Many e-learning designers these days are not formally trained in Instructional Design and initially think of it as instructional “writing” more than the holistic and systemic approach at the heart of ADDIE. Likewise, customers and subject matter experts are much easier to work with once they understand the broad project process that ADDIE represents. For these two purposes alone I am thankful for ADDIE as a framework. ADDIE has staying power because of its simplicity. Purists will say it has been watered down too much but in many ways that’s what keeps it alive.

ADDIE phases are also a useful way to think about organization design and structure of a learning function. They are the major processes that need to be managed and measured by most learning functions. Just think of the functionality of most LMS systems have added since their inception.

In the end, ADDIE (and its more current modifications) is probably most valuable because it makes the work of learning design visible. This is an essential feature of productive knowledge work of all kinds. Almost every learning/training group uses an ADDIE as a start point to design a customized process that can be communicated, executed, measured and repeated with some level of consistency. Equally important in knowledge work is the discipline of continually improving processes and breaking through to better ways of working. This has resulted in the many innovations and improvement to the ADDIE process since its inception.

SUMMATIVE EVALUATION (Phase E, Step 5.2.3)

I’ve come to believe that the power of ADDIE/ISD lies in the mind and artful hands of the user. In my experience, Rapid Application Development processes can become just as rigid and prescriptive under the watch of inflexible and bureaucratic leaders as ADDIE did.

There’s an intellectual fashion and political correctness at work in some of the outright rejection of ADDIE. It’s just not cool to associate with the stodgy old process. Add Web 2.0, informal and social learning to the mix and some will argue we shouldn’t be designing anything.

For the organizations I work with, there is no end on the horizon to formal learning (adjustments in volume and quality would be nice!). Formal learning will always require intelligent authentic learning design, and a process to make it happen as quickly and effectively as possible.

We all make mistakes. We know better, but we follow old ways or accept cultural practices that don’t work. There are patterns that produce successful projects and those that lead to failure (see the project death march). I did a recent presentation on the classic mistakes we make in the planning, design and implementation of learning (and how to avoid them). I finished the session with a with a tongue-in-cheek 7 step prescription for a failed learning initiative. Follow them carefully for guaranteed failure.

We all make mistakes. We know better, but we follow old ways or accept cultural practices that don’t work. There are patterns that produce successful projects and those that lead to failure (see the project death march). I did a recent presentation on the classic mistakes we make in the planning, design and implementation of learning (and how to avoid them). I finished the session with a with a tongue-in-cheek 7 step prescription for a failed learning initiative. Follow them carefully for guaranteed failure.