We all make mistakes. We know better, but we follow old ways or accept cultural practices that don’t work. There are patterns that produce successful projects and those that lead to failure (see the project death march). I did a recent presentation on the classic mistakes we make in the planning, design and implementation of learning (and how to avoid them). I finished the session with a with a tongue-in-cheek 7 step prescription for a failed learning initiative. Follow them carefully for guaranteed failure.

We all make mistakes. We know better, but we follow old ways or accept cultural practices that don’t work. There are patterns that produce successful projects and those that lead to failure (see the project death march). I did a recent presentation on the classic mistakes we make in the planning, design and implementation of learning (and how to avoid them). I finished the session with a with a tongue-in-cheek 7 step prescription for a failed learning initiative. Follow them carefully for guaranteed failure.

Step 1: Ensure your program is not connected to a business or performance need

A critical first step. If your learning initiative in any way contributes to individual or organization performance you’re risking success. Market your program as urgent and essential to convince your audience they need it (while you’re at it, it’s best if you can convince yourself too). You then have the option to bury the program somewhere deep in your corporate training catalog or roll it out aggressively as a mandatory program. Both tactics are equally effective at failing dismally.

Step 2: Rely on your fave management training vendor for program content

Some say learning programs should be driven by real job or role requirements–that the context in which people work should be the source for learning content. Don’t believe it. Instead, close your door, pick up the phone and call your favourite training vendor. Ask them what training you should be providing this year. They will have the answer you need and a program with all sorts of great content ready to go. Another option would be to simply gather as much content as you can from the internet. Have you seen how much information is out there!

Step 3: Choose a solution that suits you rather than your learners

There’s so many ways to deliver and support learning now. Gone are the days where your only option was a classroom training program. You probably have your favourite. Trust your gut. Go with that favourite. It will be more interesting for you. Just be sure your choice is detached from the preferences of your audience.

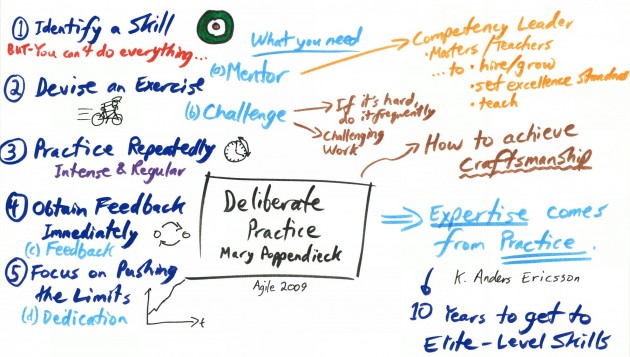

Step 4: Load up on information. Make no provision for practice

Information driven learning is one of the best strategies for failure we know of. Designing practice is hard. Even harder to design practice that works–on the job activities that develop skill in context. So don’t sweat it. There are great examples out there of power point driven classroom learning, “click next” e-learning, and social learning that’s all about sharing information without actually using any of it. Mimic those examples and you’ll get closer to putting the nail in the coffin of your failed project. But your not quite there yet.

Step 5: Let technology drive your solution

Technology is hip. And they tell us it’s needed to capture the attention of the digital natives entering your organization. So keep it cool. Your program must incorporate the most current devices and tech tools–tablets, smartphones and web 2.0 apps. Don’t think about how they support the objectives of your initiative.

Step 6: Boldly assume the learning will be used on the job

Your program is that good! It will be more powerful than the current barriers, lack of support and reinforcement that learners will encounter when they are back at work. Mastery was your goal and no refinement of those skills on the job will be necessary. Really.

Step 7: Develop your program in a client vacuum

Above all, do not partner with your internal customers to identify business needs or develop a plan to support them through formal or informal learning. One of the best predictors of success is working collaboratively with your client through the planning, design and development of your program. Avoid at all costs. Failure Guaranteed. You’re welcome.