During the Q&A at a recent conference session on Social Learning, a retail industry attendee asked “I have to train 300 store level associates in new product knowledge in the next three months. Is social learning really what I want?” What would your answer be?

I advocate informal and social learning when appropriate and get as excited about them as you likely do, but it’s not a panacea for all our learning woes. The current zeal around social learning solutions can distract from real performance needs (we’ve been distracted before). Social learning gets positioned as the enlightened and “correct” solution for the modern workplace. Formal learning is old, tired, and reluctantly tolerated for the vestiges of the traditional, mechanistic workplace.

But, set aside your biases one way or the other for the moment and simply think of the roles and functions you support in your organization. It will vary by industry of course, but your list is going to be some subset of the following

- Marketing

- Sales

- Product Development

- Manufacturing

- Operations

- Administration

- Service Delivery

- Order Fulfillment

- Information Technology

- Procurement

- Management and Leadership

Now think of the jobs or roles within those functions…the engineers, technicians, account executives, managers, IT specialists, health care workers, service specialists, and operations staff you support. Do they demand a singular approach to developing skill and capability necessary for their job? Is social learning or traditional skills training the most appropriate for all job types? I hope your answer is no.

Consultants have been telling us for years that traditional, mechanistic organizations are disappearing, and with them linear and routine work. There is no doubt that is the economic direction, but look around you…at the auto assembly lines, big box retail, supermarkets, call centres, healthcare technicians, administrative clerks in government, insurance, finance and elsewhere. Think about the jobs you support and you’ll see many examples of traditional work where social media based learning will simply not be feasible to quickly develop skills.

Task variety and standardization: Routine vs. knowledge work

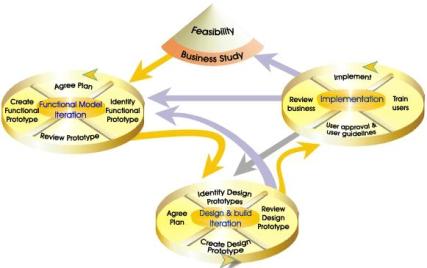

Instead of over generalizing the value of any solution it’s best to truly understand the skill and knowledge requirements of the jobs, roles or initiatives you support. I’m not talking about task or needs analysis (through both are valuable tools). Instead go up one notch higher and categorize the types of “work” you support in your organization. Almost all work, indeed entire organizations and industries, vary on a continuum of two broad factors: task variety and task standardization.

An approach for categorizing jobs, roles and work environments

In between these ends of this spectrum is work that combines standardization and task variety to different degrees. The following framework provides a classification tool to place work types, jobs and roles. It’s an adaptation of the work of Yale Organizational Sociologist Charles Perrow. Jeffrey Liker and David Meier used a different variation of this model in Toyota Talent.

Routine work

Routine work is highly standardized with little task variety. Job fundamentals need to be learned quickly and performed to company or industry defined standards. There is little room for variation and the skills that need to be learned are narrow and focused. Progressive workplaces will also involve workers in problems solving and continuous process improvement where experience will result in tacit knowledge in problem recognition and problem solving than can be shared with others through informal vehicles.

Sample jobs and roles:

- Assembly line workers

- Bank teller

- Data entry clerk

- Oil and gas well drillers

- Machine operators

- Fast food server

Learning approach:

- Formal structured, job specific skills training, performance support tools that enable standardized procedures

Technician work

The work of the technician is less standardized and includes more variety in the tasks and skills required by the role. Work still has many defined procedures and processes. However, they are more complex and often based on sophisticated systems and technology. The sequence can vary depending on the situation so employees have more autonomy in selecting appropriate procedures. There’s also greater variety in the procedures and tasks to be completed and as a result the learning programs need to consider problem solving, decision making and continuous improvement. Tacit knowledge will be needed to solve real technical problems that arise and there is often a service element in technician work that can benefit from informal approaches to learning. Performance supports system are a natural fit for technician oriented work as is mobile learning for customer support technicians often working at customer locations.

Sample jobs and roles:

- Lab analyst

- Quality Control Specialists

- Radiation technologist

- Maintenance workers

- Technical support specialists

- Most “trade” occupations

Learning approach:

- Formal structured learning for required procedures, performance support systems. Informal learning and apprenticeship approaches for building “know-how” and problem solving

Craft work

Craft oriented work introduces even greater amounts of variety in tasks, skills and knowledge, but retains significant amounts of standardization for optimal performance. While there is a definable number of tasks, each situation faced by employees is somewhat different, and each requires creative and slightly unique solutions. Over time patterns in problems and solutions emerge for individual employees and this becomes valuable experience (tacit knowledge) that they can pass on to novice employees through informal approaches. Basic skills and procedures are most efficiently taught through formal methods but the most critical parts of the job are learning through years of experience facing multiple situations. Management is more flexible and with fewer rules and formal policies. Teamwork and communications are paramount.

Sample jobs and roles:

- Nurse

- Sales professional

- Call centre agent

- Graphic designer

- Air traffic controller

- First level supervisor

- Insurance administrator

Learning approach:

Formal learning for foundation procedures and skills. Informal learning and deep work experience and mentoring models for tacit knowledge.

Knowledge work

Finally, knowledge work involves little task standardization (although there is always some) and a great amount of task variety requiring a wide range of skills, knowledge and collaboration. Professionals move from task to task and each situation is unique calling for spontaneous thinking, reasoning and decision making. Knowledge workers must adapt to new situations, assess complex data and make complex decisions. They also need refined people skills. The most critical aspects of what experts and knowledge workers do (after formal education) can only be learned on the job over time through experience, mentors and knowledge sharing with other professionals.

Sample jobs and roles:

- Professional engineers

- Middle and senior management

- Professions: Law, Medicine, Architecture, Scientists, Professors etc.

- Software developers

- Creative director

Learning approach:

Professional education, extensive job experience on a variety of situations and work assignments, action learning, mentorship, Communities of Practice.

Balanced approaches

Of course most work requires a combination of knowledge work and routine work. These characteristics of jobs and work environments call for different approaches to training and development. There is a continuum of learning solutions that range from formal to non-formal to informal. I’ve posted my view on this continuum in the past (Leveraging the full learning continuum).

Avoid over generalizing your solutions at all costs. Participate in social media and learn it’s value to develop tacit knowledge and create new knowledge in your organization but don’t assume it is the “correct” solution for all your audiences. Start with the functions you serve. Truly understand work that is done by the jobs and roles within those groups and the skills necessary for them to be successful. Only then create a solution that will meet those needs.