For years the eLearning industry has categorized custom solutions into three or more levels of interactivity– from basic to complex, simple to sophisticated. The implication also being that that learning effectiveness increases with each higher level of interactivity.

You don’t have to look hard to find them:

Levels of Interactivity in eLearning: Which one do you need?

How Long Does it Take to Create Learning?

These kinds of categorizations surely originated in the vendor community as they sought ways to productize custom development and make it easier for customers to buy standard types of e-learning. I won’t quibble that “Levels of interactivity” has helped simplify the selling/buying process in the past but it’s starting to outlive it’s usefulness. And they are a disservice to intelligent buyers of e-learning. Here’s why:

1. The real purpose is price standardization

Levels of interactivity are usually presented as a way to match e-learning level to learning goals. You’ve seen it–Level 1 basic/rapid is best for information broadcast, level 2 for knowledge development and level 3 and beyond for behaviour change or something to that effect. However, in reality very simple, well designed low end e-learning can change behavior and high end e-learning programs can wow while provide no learning impact whatsoever.

If vendors were honest the real purpose of “levels of interactivity” is to standardize pricing into convenient blocks to make e-learning easier to sell and purchase. “How much is an hour of level 2 e-learning again? OK, I’ll take three of those please”. each level of e-learning comes with a pre-defined scope that vendors can put a ready price tag on.

It’s a perfectly acceptable product positioning strategy, but it’s not going to get you the best solution to resolving your skill or knowledge issue.

2. Interactivity levels artificially cluster e-learning features and in doing so reduce choice

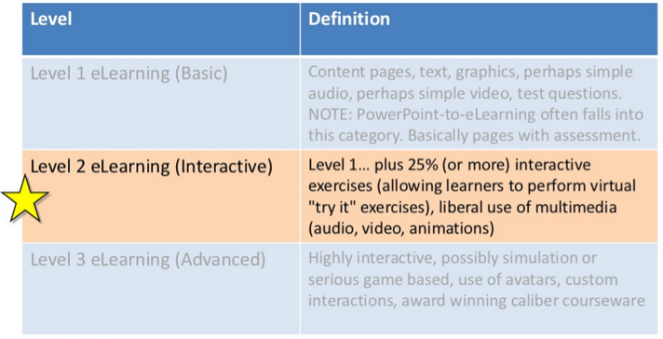

Most definitions of what features are included in each of the “levels” are vague at best. Try this definition from Brandon Hall in wide use:

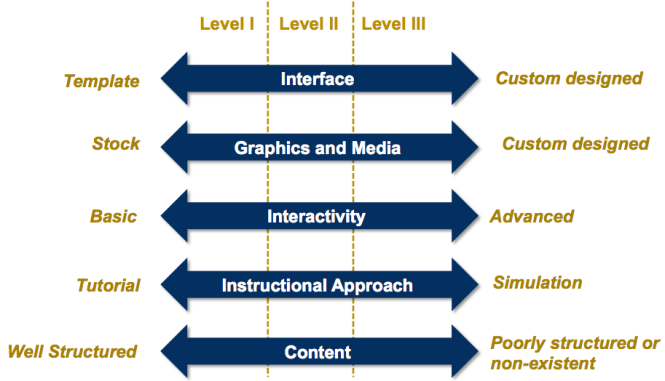

It’s hard to imagine looser definitions of each level. In fact there are a variety of factors that drive scope and effort (and therefore price) in a custom e-learning program. And they go well beyond “interactivity”. They include interface choices, type and volume of graphics and media, instructional strategies, existence and quality of current content, and yes, the type and complexity of user interactions.

Each of these features has a range of choices within them, but the levels of interactivity approach tends to cluster everything into one bucket and call it a level. It might look something like the following:

A Level 1 program is essentially a template based page turner with a few relevant (or maybe not so relevant) stock images and interactivity limited to some standard multiple choice self checks. In contrast, a Level III program is loaded with custom designed interface, user controls, media and graphics, along with with complex interactions assumed to be required for simulations and scenarios. Level 2 is the middle choice most buyers and vendors alike are happy to land on. None of these choices, by the way, has anything to do with accomplishing a desired learning outcome–but that’s another discussion.

If this artificial clustering of features was ever true, it’s not any longer. Advanced simulations and scenarios can be created with very basic media and user interface features. Advanced custom interface and controls with rich custom media are often used to support simple information presentation with very little interactivity. Powerful scenario based learning can be created with simple levels of interactivity. Rapid e-learning tools once relegated to the Level 1 ghetto, can create quite advanced programs and custom HTML/Flash can just as easily churn out page turners. Out-of-the box avatars can be created in minutes.

This clustering of features into three groups gives you less choice that you would receive at your local Starbucks. If I’m a customer with a learning objective that is best served by well produced video and animations followed by an on the job application exercise, I’m not sure what level I would be choosing. A good e-learning vendor will discuss and incorporate these options into a price model that matches the customer requirement.

3. It reduces effectiveness and creativity

Forcing solutions into one of three or four options stunts creative thinking and pushed the discussion towards media and interactivity rather than closing a skill gap where it should be.

4. It hurts informed decision making

It appears to create a common language but actually reinforces the myth that there are only three or four types of e-learning. The combinations of media, interactivity and instructional approaches are as varied as the skill and knowledge gaps they are meant to address.

5. It encourages a narrow vision of e-learning

e-Learning has morphed into new forms. Pure e-learning is already in decline being cannibalized by mobile and social learning and the glorious return of performance support. These approaches are much more flexible and nimble at addressing knowledge and skill gaps.